Can the President Declare Martial Law Without Congress

The Alarming Scope of the President's Emergency Powers

From seizing control of the internet to declaring martial constabulary, President Trump may legally practice all kinds of boggling things.

Inorth the weeks leading up to the 2022 midterm elections, President Donald Trump reached deep into his arsenal to endeavor to deliver votes to Republicans.

About of his weapons were rhetorical, featuring a mix of lies and false inducements—claims that every congressional Democrat had signed on to an "open up borders" bill (none had), that liberals were fomenting trigger-happy "mobs" (they weren't), that a 10 percent taxation cut for the middle class would somehow pass while Congress was out of session (it didn't). But a few involved the aggressive use—and threatened misuse—of presidential say-so: He sent thousands of agile-duty soldiers to the southern border to terrorize a distant caravan of desperate Central American migrants, announced plans to end the constitutional guarantee of birthright citizenship by executive social club, and tweeted that police force enforcement had been "strongly notified" to be on the scout for "ILLEGAL VOTING."

These measures failed to behave the day, and Trump volition likely conclude that they were too timid. How much farther might he go in 2020, when his own name is on the ballot—or sooner than that, if he'due south facing impeachment past a Firm under Autonomous control?

More is at stake here than the upshot of one or even two elections. Trump has long signaled his disdain for the concepts of limited presidential power and democratic rule. During his 2022 entrada, he praised murderous dictators. He declared that his opponent, Hillary Clinton, would be in jail if he were president, goading crowds into frenzied chants of "Lock her up." He hinted that he might not accept an electoral loss. As democracies around the world slide into autocracy, and nationalism and antidemocratic sentiment are on brilliant display among segments of the American populace, Trump'due south evident hostility to key elements of liberal democracy cannot be dismissed as mere bluster.

It would exist nice to think that America is protected from the worst excesses of Trump'south impulses by its democratic laws and institutions. Later on all, Trump tin can do only then much without bumping upward against the limits set by the Constitution and Congress and enforced by the courts. Those who run across Trump equally a threat to democracy comfort themselves with the belief that these limits will concur him in bank check.

But will they? Unknown to most Americans, a parallel legal regime allows the president to sidestep many of the constraints that unremarkably utilize. The moment the president declares a "national emergency"—a decision that is entirely within his discretion—more than 100 special provisions become available to him. While many of these tee upwardly reasonable responses to genuine emergencies, some appear dangerously suited to a leader aptitude on amassing or retaining ability. For instance, the president can, with the moving picture of his pen, activate laws allowing him to shut downward many kinds of electronic communications inside the Usa or freeze Americans' bank accounts. Other powers are available even without a annunciation of emergency, including laws that permit the president to deploy troops inside the state to subdue domestic unrest.

This edifice of extraordinary powers has historically rested on the assumption that the president will act in the country'due south best interest when using them. With a handful of noteworthy exceptions, this assumption has held upwards. Just what if a president, backed into a corner and facing balloter defeat or impeachment, were to declare an emergency for the sake of holding on to power? In that scenario, our laws and institutions might non save us from a presidential power grab. They might exist what takes us downwards.

1. "A LOADED WEAPON"

The premise underlying emergency powers is simple: The regime'southward ordinary powers might be insufficient in a crisis, and amending the police to provide greater ones might be likewise slow and cumbersome. Emergency powers are meant to give the government a temporary boost until the emergency passes or there is time to modify the police through normal legislative processes.

Unlike the modern constitutions of many other countries, which specify when and how a country of emergency may be declared and which rights may be suspended, the U.S. Constitution itself includes no comprehensive separate regime for emergencies. Those few powers it does contain for dealing with sure urgent threats, it assigns to Congress, non the president. For instance, information technology lets Congress suspend the writ of habeas corpus—that is, allow government officials to imprison people without judicial review—"when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may crave it" and "provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Marriage, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions."

Nonetheless, some legal scholars believe that the Constitution gives the president inherent emergency powers by making him commander in main of the armed services, or by vesting in him a broad, undefined "executive Power." At key points in American history, presidents take cited inherent constitutional powers when taking drastic actions that were not authorized—or, in some cases, were explicitly prohibited—past Congress. Notorious examples include Franklin D. Roosevelt'southward internment of U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent during World War Two and George W. Bush's programs of warrantless wiretapping and torture after the 9/eleven terrorist attacks. Abraham Lincoln conceded that his unilateral suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War was constitutionally questionable, just defended it as necessary to preserve the Union.

The Supreme Court has often upheld such actions or found ways to avoid reviewing them, at least while the crisis was in progress. Rulings such as Youngstown Sheet & Tube Visitor v. Sawyer, in which the Courtroom invalidated President Harry Truman's bid to take over steel mills during the Korean War, accept been the exception. And while those exceptions have outlined important limiting principles, the outer boundary of the president'south constitutional authorization during emergencies remains poorly divers.

Presidents can too rely on a cornucopia of powers provided by Congress, which has historically been the primary source of emergency authorisation for the executive co-operative. Throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries, Congress passed laws to give the president additional elbowroom during military, economical, and labor crises. A more formalized approach evolved in the early on 20th century, when Congress legislated powers that would lie dormant until the president activated them past declaring a national emergency. These statutory authorities began to pile up—and because presidents had little incentive to terminate states of emergency once alleged, these piled up too. Past the 1970s, hundreds of statutory emergency powers, and iv clearly obsolete states of emergency, were in outcome. For case, the national emergency that Truman alleged in 1950, during the Korean War, remained in place and was being used to help prosecute the war in Vietnam.

Aiming to rein in this proliferation, Congress passed the National Emergencies Act in 1976. Under this law, the president still has complete discretion to issue an emergency declaration—but he must specify in the declaration which powers he intends to use, issue public updates if he decides to invoke additional powers, and study to Congress on the regime'southward emergency-related expenditures every six months. The state of emergency expires after a year unless the president renews information technology, and the Senate and the Firm must encounter every six months while the emergency is in effect "to consider a vote" on termination.

By whatever objective measure out, the constabulary has failed. Thirty states of emergency are in result today—several times more than when the human activity was passed. Well-nigh accept been renewed for years on end. And during the 40 years the police has been in place, Congress has not met even once, permit alone every half-dozen months, to vote on whether to end them.

As a issue, the president has admission to emergency powers contained in 123 statutory provisions, as recently calculated by the Brennan Eye for Justice at NYU Schoolhouse of Law, where I work. These laws address a broad range of matters, from military composition to agricultural exports to public contracts. For the most part, the president is free to use whatsoever of them; the National Emergencies Act doesn't require that the powers invoked relate to the nature of the emergency. Fifty-fifty if the crisis at mitt is, say, a nationwide ingather blight, the president may actuate the law that allows the secretary of transportation to requisition whatever privately owned vessel at sea. Many other laws let the executive branch to accept extraordinary activity under specified weather, such as state of war and domestic upheaval, regardless of whether a national emergency has been declared.

This legal regime for emergencies—ambiguous ramble limits combined with a rich well of statutory emergency powers—would seem to provide the ingredients for a dangerous encroachment on American civil liberties. Yet so far, fifty-fifty though presidents have often avant-garde dubious claims of constitutional dominance, egregious abuses on the scale of the Japanese American internment or the post-9/11 torture programme have been rare, and almost of the statutory powers available during a national emergency have never been used.

But what'due south to guarantee that this president, or a hereafter i, will prove the reticence of his predecessors? To borrow from Justice Robert Jackson's dissent in Korematsu 5. United States, the 1944 Supreme Court conclusion that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans, each emergency power "lies about similar a loaded weapon, set for the hand of whatever authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent demand."

2. AN Net Kill SWITCH?

Like all emergency powers, the laws governing the conduct of state of war allow the president to engage in conduct that would be illegal during ordinary times. This behave includes familiar incidents of war, such every bit the killing or indefinite detention of enemy soldiers. Merely the president can besides take a host of other actions, both abroad and inside the United states of america.

These laws vary dramatically in content and telescopic. Several of them authorize the president to make decisions about the size and limerick of the military that are ordinarily left to Congress. Although such measures tin offer needed flexibility at crucial moments, they are subject to misuse. For instance, George West. Bush-league leveraged the state of emergency after 9/eleven to call hundreds of thousands of reservists and members of the National Guard into agile duty in Republic of iraq, for a war that had nothing to practice with the nine/eleven attacks. Other powers are spooky under whatsoever circumstances: Take a moment to consider that during a declared war or national emergency, the president tin unilaterally suspend the law that bars government testing of biological and chemical agents on unwitting human subjects.

One power poses a singular threat to democracy in the digital era. In 1942, Congress amended Section 706 of the Communications Human action of 1934 to let the president to close down or take command of "any facility or station for wire communication" upon his proclamation "that there exists a state or threat of war involving the United States," resurrecting a similar power Congress had briefly provided Woodrow Wilson during Globe State of war I. At the fourth dimension, "wire communication" meant telephone calls or telegrams. Given the relatively modest role that electronic communications played in virtually Americans' lives, the government'southward assertion of this power during World State of war II (no president has used information technology since) likely created inconvenience but not havoc.

Nosotros live in a dissimilar universe today. Although interpreting a 1942 police to cover the internet might seem far-fetched, some authorities officials recently endorsed this reading during debates about cybersecurity legislation. Under this interpretation, Section 706 could effectively office as a "kill switch" in the U.Due south.—one that would be bachelor to the president the moment he proclaimed a mere threat of state of war. It could too give the president power to presume control over U.S. internet traffic.

The potential touch of such a move can inappreciably be overstated. In August, in an early-morning tweet, Trump lamented that search engines were "RIGGED" to serve up negative articles about him. Later on that day the assistants said it was looking into regulating the big internet companies. "I recollect that Google and Twitter and Facebook, they're really treading on very, very troubled territory. And they have to exist careful," Trump warned. If the government were to take control of U.S. internet infrastructure, Trump could accomplish directly what he threatened to do by regulation: ensure that cyberspace searches always render pro-Trump content as the top results. The government too would take the ability to impede domestic access to particular websites, including social-media platforms. It could monitor emails or preclude them from reaching their destination. Information technology could exert control over computer systems (such as states' voter databases) and concrete devices (such as Amazon's Echo speakers) that are connected to the net.

Video: Trump's Emergency Powers Are "Ripe for Abuse"

To be sure, the fact that the internet in the Usa is highly decentralized—a function of a relatively open market for communications devices and services—would offering some protection. Achieving the level of regime control over internet content that exists in places such as China, Russia, and Iran would likely be impossible in the U.Southward. Moreover, if Trump were to attempt any degree of internet takeover, an explosion of lawsuits would follow. Based on its First Amendment rulings in recent decades, the Supreme Court seems unlikely to permit heavy-handed government control over net advice.

But complacency would be a mistake. Complete command of internet content would non be necessary for Trump's purposes; fifty-fifty with less comprehensive interventions, he could practice a great deal to disrupt political discourse and hinder effective, organized political opposition. And the Supreme Courtroom's view of the Starting time Amendment is non immutable. For much of the country'south history, the Court was willing to tolerate significant encroachments on free speech during wartime. "The progress we take made is fragile," Geoffrey R. Stone, a ramble-police scholar at the University of Chicago, has written. "Information technology would not take much to upset the current understanding of the First Amendment." Indeed, all it would take is v Supreme Court justices whose delivery to presidential ability exceeds their delivery to individual liberties.

3. SANCTIONING AMERICANS

Next to war powers, economic powers might sound benign, but they are among the president's most potent legal weapons. All but ii of the emergency declarations in event today were issued under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or ieepa. Passed in 1977, the law allows the president to declare a national emergency "to bargain with whatsoever unusual and extraordinary threat"—to national security, foreign policy, or the economic system—that "has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States." The president can so order a range of economic deportment to address the threat, including freezing assets and blocking financial transactions in which any foreign nation or foreign national has an interest.

In the late 1970s and '80s, presidents used the law primarily to impose sanctions against other nations, including Iran, Nicaragua, South Africa, Great socialist people's libyan arab jamahiriya, and Panama. Then, in 1983, when Congress failed to renew a law authorizing the Commerce Department to control certain exports, President Ronald Reagan declared a national emergency in club to assume that control under ieepa. Subsequent presidents followed his example, transferring export control from Congress to the White Firm. President Neb Clinton expanded ieepa'south usage by targeting non just foreign governments just strange political parties, terrorist organizations, and suspected narcotics traffickers.

President George Westward. Bush took matters a giant step further after 9/xi. His Executive Order 13224 prohibited transactions not just with any suspected strange terrorists, but with any foreigner or any U.S. citizen suspected of providing them with back up. Once a person is "designated" nether the order, no American tin can legally requite him a task, rent him an flat, provide him with medical services, or even sell him a loaf of staff of life unless the authorities grants a license to allow the transaction. The patriot Human activity gave the order more muscle, allowing the government to trigger these consequences merely by opening an investigation into whether a person or group should be designated.

Designations under Executive Order 13224 are opaque and extremely hard to challenge. The government needs just a "reasonable ground" for believing that someone is involved with or supports terrorism in order to designate him. The target is generally given no advance notice and no hearing. He may asking reconsideration and submit show on his behalf, but the government faces no deadline to respond. Moreover, the testify against the target is typically classified, which means he is not allowed to see it. He tin try to claiming the activity in court, but his chances of success are minimal, as most judges defer to the government'due south assessment of its own evidence.

Americans accept occasionally been caught up in this Kafkaesque system. Several Muslim charities in the U.S. were designated or investigated based on the suspicion that their charitable contributions overseas benefited terrorists. Of course if the regime can show, through judicial proceedings that find due process and other constitutional rights, that an American group or person is funding terrorist activity, it should be able to cutting off those funds. But the government shut these charities downward by freezing their assets without always having to prove its charges in court.

In other cases, Americans were significantly harmed by designations that later proved to exist mistakes. For example, two months later nine/11, the Treasury Section designated Garad Jama, a Somalian-born American, based on an erroneous determination that his money-wiring business was part of a terror-financing network. Jama's function was shut down and his bank account frozen. News outlets described him as a suspected terrorist. For months, Jama tried to gain a hearing with the authorities to establish his innocence and, in the meantime, obtain the government's permission to get a chore and pay his lawyer. Just later on he filed a lawsuit did the regime let him to work every bit a grocery-shop cashier and pay his living expenses. It was several more than months before the government reversed his designation and unfroze his assets. Past then he had lost his business, and the stigma of having been publicly labeled a terrorist supporter continued to follow him and his family.

Despite these dramatic examples, ieepa'southward limits have yet to be fully tested. Afterward two courts ruled that the government'due south actions against American charities were unconstitutional, Barack Obama'due south administration chose not to appeal the decisions and largely refrained from further controversial designations of American organizations and citizens. Thus far, President Trump has followed the aforementioned approach.

That could change. In October, in the pb-up to the midterm elections, Trump characterized the caravan of Fundamental American migrants headed toward the U.S. border to seek asylum as a "National Emergency." Although he did non issue an emergency proclamation, he could do and so under ieepa. He could determine that any American inside the U.S. who offers material back up to the asylum seekers—or, for that matter, to undocumented immigrants within the U.s.—poses "an unusual and extraordinary threat" to national security, and authorize the Treasury Department to take activeness against them.

Such a movement would bear echoes of a law passed recently in Republic of hungary that criminalized the provision of fiscal or legal services to undocumented migrants; this has been dubbed the "Stop Soros" law, later on the Hungarian American philanthropist George Soros, who funds migrants'-rights organizations. Although an order issued under ieepa would not country targets in jail, information technology could be implemented without legislation and without affording targets a trial. In practice, identifying every American who has hired, housed, or provided paid legal representation to an aviary seeker or undocumented immigrant would be impossible—just all Trump would need to practice to achieve the desired political effect would exist to make high-profile examples of a few. Individuals targeted by the gild could lose their jobs, and find their bank accounts frozen and their health insurance canceled. The boxing in the courts would then choice upwards exactly where information technology left off during the Obama assistants—merely with a newly reconstituted Supreme Court making the final phone call.

4. BOOTS ON MAIN STREET

The thought of tanks rolling through the streets of U.S. cities seems fundamentally inconsistent with the country'due south notions of democracy and liberty. Americans might be surprised, therefore, to larn only how readily the president tin deploy troops within the country.

The principle that the military should not human action every bit a domestic police force, known as "posse comitatus," has deep roots in the nation's history, and it is often mistaken for a constitutional rule. The Constitution, still, does not prohibit military participation in police activity. Nor does the Posse Comitatus Human action of 1878 outlaw such participation; it but states that any potency to employ the war machine for law-enforcement purposes must derive from the Constitution or from a statute.

The Insurrection Act of 1807 provides the necessary authorisation. As amended over the years, it allows the president to deploy troops upon the asking of a state's governor or legislature to help put down an coup inside that state. It too allows the president to deploy troops unilaterally, either because he determines that rebellious activity has fabricated it "impracticable" to enforce federal constabulary through regular means, or considering he deems it necessary to suppress "insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy" (terms non defined in the statute) that hinders the rights of a course of people or "impedes the course of justice."

Presidents accept wielded the Insurrection Deed nether a range of circumstances. Dwight Eisenhower used it in 1957 when he sent troops into Picayune Rock, Arkansas, to enforce school desegregation. George H. Westward. Bush employed information technology in 1992 to assist cease the riots that erupted in Los Angeles later the verdict in the Rodney King instance. George W. Bush considered invoking it to help restore public guild after Hurricane Katrina, but opted confronting information technology when the governor of Louisiana resisted federal control over the land's National Guard. While controversy surrounded all these examples, none suggests obvious overreach.

And yet the potential misuses of the act are legion. When Chicago experienced a spike in homicides in 2017, Trump tweeted that the urban center must "fix the horrible 'carnage' " or he would "send in the Feds!" To conduct out this threat, the president could declare a particular street gang—say, MS‑thirteen—to be an "unlawful combination" and then send troops to the nation'south cities to police the streets. He could narrate sanctuary cities—cities that refuse to provide assistance to clearing-enforcement officials—as "conspiracies" against federal authorities, and club the military to enforce immigration laws in those places. Conjuring the specter of "liberal mobs," he could send troops to suppress alleged rioting at the fringes of anti-Trump protests.

How far could the president become in using the military within U.S. borders? The Supreme Court has given united states of america no clear answer to this question. Have Ex parte Milligan, a famous ruling from 1866 invalidating the use of a war machine commission to endeavour a civilian during the Civil War. The case is widely considered a high-water mark for judicial constraint on executive activity. Yet even as the Court held that the president could not use war or emergency as a reason to featherbed civilian courts, it noted that martial law—the deportation of civilian say-so by the military—would be appropriate in some cases. If civilian courts were closed as a result of a strange invasion or a civil war, for example, martial constabulary could be "until the laws tin can accept their gratuitous form." The message is incomparably mixed: Claims of emergency or necessity cannot legitimize martial law … until they tin.

Presented with this ambiguity, presidents have explored the outer limits of their constitutional emergency authority in a series of directives known as Presidential Emergency Activeness Documents, or peads. peads, which originated as function of the Eisenhower administration'due south plans to ensure continuity of government in the wake of a Soviet nuclear attack, are draft executive orders, proclamations, and messages to Congress that are prepared in accelerate of anticipated emergencies. peads are closely guarded within the government; none has e'er been publicly released or leaked. Merely their contents take occasionally been described in public sources, including FBI memorandums that were obtained through the Freedom of Data Human activity likewise as bureau manuals and court records. According to these sources, peads drafted from the 1950s through the 1970s would authorize not only martial police but the suspension of habeas corpus by the executive branch, the revocation of Americans' passports, and the roundup and detention of "subversives" identified in an FBI "Security Index" that independent more than ten,000 names.

Less is known about the contents of more recent peads and equivalent planning documents. But in 1987, The Miami Herald reported that Lieutenant Colonel Oliver Northward had worked with the Federal Emergency Management Bureau to create a undercover contingency program authorizing "suspension of the Constitution, turning control of the Us over to fema, appointment of military machine commanders to run state and local governments and proclamation of martial constabulary during a national crisis." A 2007 Department of Homeland Security report lists "martial police force" and "curfew declarations" as "critical tasks" that local, state, and federal government should be able to perform in emergencies. In 2008, government sources told a reporter for Radar magazine that a version of the Security Index still existed under the code name Main Cadre, allowing for the apprehension and detention of Americans tagged as security threats.

Since 2012, the Department of Justice has been requesting and receiving funds from Congress to update several dozen peadsouthward first developed in 1989. The funding requests contain no indication of what these peaddue south encompass, or what standards the department intends to utilise in reviewing them. Only any the Obama administration's intent, the review has now passed to the Trump administration. It volition fall to Jeff Sessions's successor as attorney general to decide whether to rein in or expand some of the more frightening features of these peads. And, of course, it will be up to President Trump whether to actually use them—something no previous president appears to have done.

5. KINDLING AN EMERGENCY

Wlid would the Founders call back of these and other emergency powers on the books today, in the easily of a president like Donald Trump? In Youngstown, the case in which the Supreme Courtroom blocked President Truman's endeavour to seize the nation's steel mills, Justice Jackson observed that wide emergency powers were "something the forefathers omitted" from the Constitution. "They knew what emergencies were, knew the pressures they engender for administrative activeness, knew, too, how they afford a ready pretext for usurpation," he wrote. "We may as well suspect that they suspected that emergency powers would tend to kindle emergencies."

In the past several decades, Congress has provided what the Constitution did not: emergency powers that have the potential for creating emergencies rather than ending them. Presidents have congenital on these powers with their ain undercover directives. What has prevented the wholesale abuse of these regime until at present is a baseline commitment to liberal democracy on the office of by presidents. Nether a president who doesn't share that commitment, what might we see?

Imagine that it'south belatedly 2019. Trump's approval ratings are at an all-time low. A disgruntled one-time employee has leaked documents showing that the Trump Organization was involved in illegal business dealings with Russian oligarchs. The trade state of war with China and other countries has taken a significant toll on the economic system. Trump has been caught in one case again disclosing classified information to Russian officials, and his international gaffes are becoming impossible for lawmakers concerned near national security to ignore. A few of his Republican supporters in Congress brainstorm to distance themselves from his assistants. Back up for impeachment spreads on Capitol Hill. In harbinger polls pitting Trump against various potential Democratic presidential candidates, the Democrat consistently wins.

Trump reacts. Unfazed by his own brazen hypocrisy, he tweets that Iran is planning a cyber operation to interfere with the 2022 ballot. His national-security adviser, John Bolton, claims to take seen ironclad (only highly classified) evidence of this planned attack on U.Due south. democracy. Trump'southward inflammatory tweets provoke predictable saber rattling past Iranian leaders; he responds by threatening preemptive military strikes. Some Defense Department officials take misgivings, but others have been waiting for such an opportunity. As Iran's statements grow more warlike, "Iranophobia" takes hold amid the American public.

Proclaiming a threat of war, Trump invokes Section 706 of the Communications Human action to presume authorities control over internet traffic inside the United States, in order to prevent the spread of Iranian disinformation and propaganda. He likewise declares a national emergency under ieepa, authorizing the Treasury Department to freeze the assets of any person or organization suspected of supporting Iran'southward activities against the United States. Wielding the authority conferred by these laws, the regime shuts downward several left-leaning websites and domestic civil-order organizations, based on government determinations (classified, of form) that they are subject to Iranian influence. These include websites and organizations that are focused on getting out the vote.

Lawsuits follow. Several judges issue orders declaring Trump'due south actions unconstitutional, but a handful of judges appointed by the president side with the administration. On the eve of the election, the cases reach the Supreme Court. In a 5–4 opinion written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the Court observes that the president's powers are at their zenith when he is using authority granted by Congress to protect national security. Setting new precedent, the Court holds that the First Amendment does non protect Iranian propaganda and that the government needs no warrant to freeze Americans' assets if its goal is to mitigate a foreign threat.

Protests erupt. On Twitter, Trump calls the protesters traitors and suggests (in capital messages) that they could use a expert beating. When counterprotesters oblige, Trump blames the original protesters for sparking the violent confrontations and deploys the Coup Act to federalize the National Guard in several states. Using the Presidential Warning organisation start tested in Oct 2018, the president sends a text message to every American'southward cellphone, warning that at that place is "a risk of violence at polling stations" and that "troops will be deployed as necessary" to continue club. Some members of opposition groups are frightened into staying domicile on Election Day; other people simply can't find accurate data online nigh voting. With turnout at a historical low, a president who was facing impeachment but months before handily wins reelection—and marks his victory past renewing the state of emergency.

This scenario might audio extreme. But the misuse of emergency powers is a standard gambit among leaders attempting to consolidate power. Authoritarians Trump has openly claimed to admire—including the Philippines' Rodrigo Duterte and Turkey'southward Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—have gone this route.

Of course, Trump might besides choose to act entirely outside the constabulary. Presidents with a far stronger commitment to the rule of law, including Lincoln and Roosevelt, have done exactly that, albeit in response to real emergencies. But in that location is petty that can be done in advance to stop this, other than attempting deterrence through robust oversight. The remedies for such behavior can come only afterwards the fact, via court judgments, political blowback at the voting booth, or impeachment.

By dissimilarity, the dangers posed by emergency powers that are written into statute tin exist mitigated through the simple expedient of changing the law. Committees in the Business firm could begin this procedure now by undertaking a thorough review of existing emergency powers and declarations. Based on that review, Congress could repeal the laws that are obsolete or unnecessary. Information technology could revise others to include stronger protections confronting corruption. It could consequence new criteria for emergency declarations, crave a connexion between the nature of the emergency and the powers invoked, and prohibit indefinite emergencies. Information technology could limit the powers gear up along in peads.

Congress, of course, volition undertake none of these reforms without extraordinary public pressure—and until now, the public has paid picayune heed to emergency powers. But we are in uncharted political territory. At a time when other democracies effectually the world are slipping toward authoritarianism—and when the president seems eager for the The states to follow their case—we would be wise to shore up the guardrails of liberal commonwealth. Fixing the current organization of emergency powers would be a good place to outset.

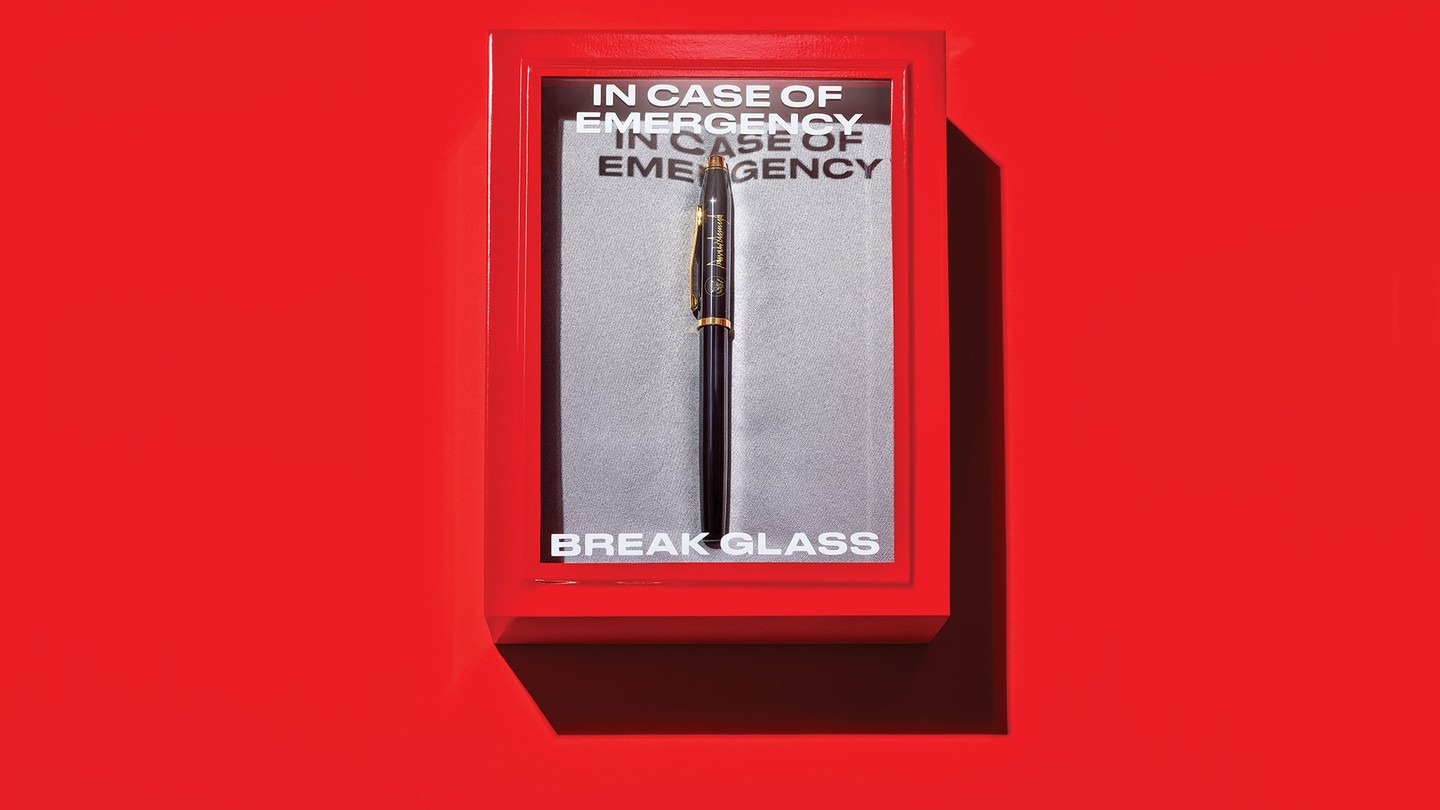

This article appears in the Jan/Feb 2022 impress edition with the headline "In Case of Emergency."

mitchelldenjudd42.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/presidential-emergency-powers/576418/

0 Response to "Can the President Declare Martial Law Without Congress"

Post a Comment